Reading Like a Writer: THE GENIUS OF JUDY

"...No would-be biographer, in my view, should embark on the depiction of a real life without bothering to know something about how--and why--previous biographers have addressed the lives of real individuals in the past--and with what results." --Nigel Hamilton, How to Do Biography: A Primer

Writers generally accept that in order to be a good writer, they need to write a lot. But many aspiring writers might not realize that they also need to read a lot as well. And when I say a lot, I mean a lot. Some writing mentors will say that you need to read at least fifty books in your genre to be versed enough in the tropes, traditions, and basic rules, not only so you can follow them, but so you can knowingly break them when it's appropriate as well.

Now, I've read far more than fifty biographies in my life, and guess what? I still feel like I learn something new about craft every time I read one. Sometimes it's something good--something I definitely want to try out some day. Other times, I learn something that I want to avoid. Regardless, reading voraciously is something I have never regretted. So I thought I would start this series about reading like a writer to maybe help others learn from what I am doing. Learn from my learning, if you will.

Anyway.

The articles in this series aren’t going to be a book reviews in the typical sense. They will be more reviews of authors' processes, to suss out what works and what doesn't so we can refine the tools in our writers' toolkits.

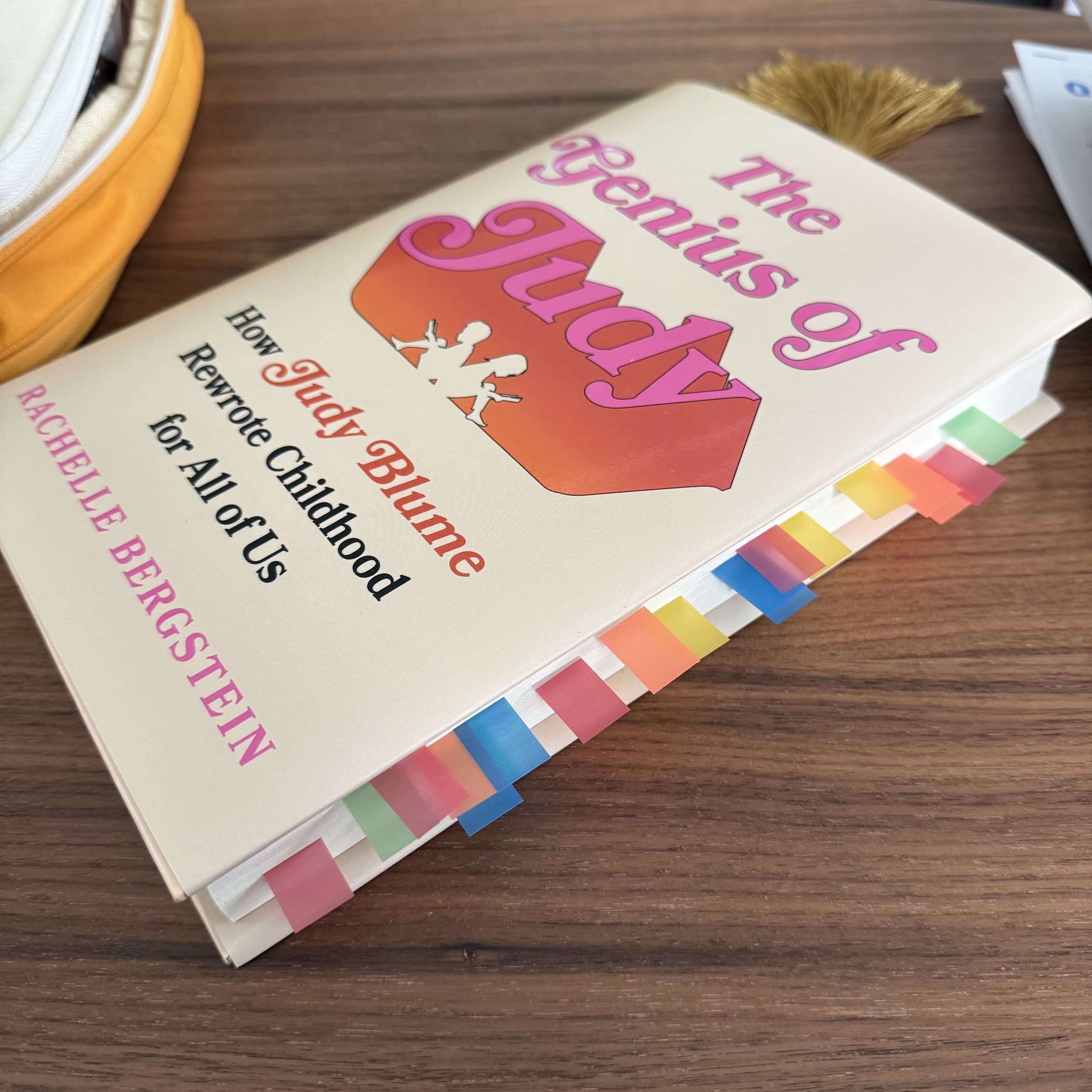

The Genius of Judy: How Judy Blume Rewrote Childhood for All of Us by Rochelle Bergstein

This book is equal parts biography, annotated bibliography, and cultural history. Bergstein does this as a conscious device to frame Blume's life, and I think she does it quite effectively. In a vacuum, Blume's life resembles a great many others and might be unremarkable, except for the fact that she is a bestselling author. But Bergstein recognized the parallels between Blume, the themes and subjects of her novels, and what was going on in the 1960s-80s, particularly involving feminism and sexuality. She embraces this and frames her whole book using these three elements.

The author uses the preface to get across why Judy Blume matters, not only to her, but to multiple generations of adolescent readers. "We need Judy Blume now because she understands this moment better than anyone." Bergstein asks the question, why is Blume so evergreen? What is her "secret ingredient?" Blume is special, she says, "Because she made young readers feel seen."

After her prologue, Bergstein then goes on to discuss second-wave feminism and the work of women's rights activists like Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan, and Kate Millet. These activists wanted to give women access to their own bodies,. To give them control over their bodies and experiences, and even their--gasp!--pleasure. Judy Blume wasn't an activist the way these others were. So what was the connection Bergstein was going for? What was the genius of Judy Blume that the title of her book hints at? Bergstein thinks it was the way she took the feminist values she absorbed during that time and translated them for young readers. Readers internalized the lessons in Blume's books--lessons that normalized their changing bodies, intense feelings, and milestones that might otherwise have been scary or disturbing. In this way, Bergstein proposes, she helped ensure feminism's longevity.

Leaders of second-wave feminism were very aware of how easily values could slide backward. They had seen it happen with their own mothers and grandmothers. The first wave suffragists had won the vote for women, but then did little to hold on to their progress. Perhaps they didn't realize how tentative their progress was, or perhaps they were just exhausted. This caused a stagnation and, after the Second World War, a regression of the social and cultural work done earlier. Second-wave feminists did not want to see this happen again, and this time they had a secret weapon they didn't even know about--a writer named Judy Blume. Bergstein spends the rest of the book supporting this argument.

Bergstein opens Chapter One, "Housewife's Syndrome," with Blume's marriage straight out of college in 1959. She then puts Blume's marriage and described experiences into the context of the early sixties, where many, if not most, people were "playacting Leave It to Beaver." Women had little to do but live for their families. Wives developed a sort of ennui--"the problem that has no name," Betty Friedan called it. Gone were the days when women entered the workforce during the War. Now, they were home once more. Many women developed depression as well as other physical ailments like rashes, aches, and other symptoms that had no obvious causes. Judy Blume was no exception to this.

Then, Blume started writing. At first, it was a diversion, something to keep her from boredom, but she kept at it until she got published. Her ailments cleared after she felt like she had a purpose in life and that she had agency over something. That was in line with many other women at the time.

Subsequent chapters of the book follow a similar structure. Bergstein discusses what was happening in Blume's life, then zooms out to put it into the context of the social change of the time. This allows readers to see the connection that makes Blume so culturally relevant. Bergstein puts Blume's books into this same framework, making Blume, her work, and the changing culture inseparable, a nuanced and complete portrait that could not exist if one piece were removed. Because of the way Bergstein weaves these things together, readers are left with no question as to why Blume is important enough to read a whole book about. Bergstein shows that Blume is relevant to people even if they know or care nothing about children's literature. There are chapters about menstruation, rebellion, divorce, sex, and more, all fitting Blume's books and life in to the larger narrative of social history. She was one of the first authors who made kids feel normal and okay about all the changes that were happening to them.

Rachelle Bergstein, author of The Genius of Judy

Then, the 1980s happened, the Reagan era and everything that came after, and that's another place where this book really shines. It wasn't enough for Bergstein to make Blume historically relevant. By focusing on censorship and book bans from both the 1980s and now, Bergstein makes the point of Blume's pertinence to today needle-sharp. Biographers can learn a lot from studying Bergstein's three-pronged approach to a person's life. Life, work, and culture are woven together seamlessly.

Because Blume is still living, I was curious as to what sources Bergstein used. It seems from her citations that she got most of her information about Blume's life from three other books: two biographies and then Blume's memoir based on the letters she received from children. Bergstein also pored over a great many interviews Blume gave to the press throughout her life. She also consulted Blume's papers at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University, though there was a condition that she could not quote directly from those sources. Though Bergstein did not interview Blume directly, she had conversations with many other people involved with Blume's story, including readers. This allowed her to develop a three-dimensional narrative.

Overall, Bergstein's approach to this book allowed her to write something that was very different from previous biographies of her subject. Many newer biographers (as well as some veterans) might worry about how to inject freshness into a subject that has been covered before. Experienced biographers might wonder how they can keep their style from stagnating or might want to try something new. All of them can learn something from The Genius of Judy.

Help make my research possible!

If you like this content and want to support its creation, please consider supporting me on Patreon! Membership levels start at $2/a month, and every little bit makes a big difference. All proceeds go toward research costs for my large-scale biography projects as well as smaller pieces like these.