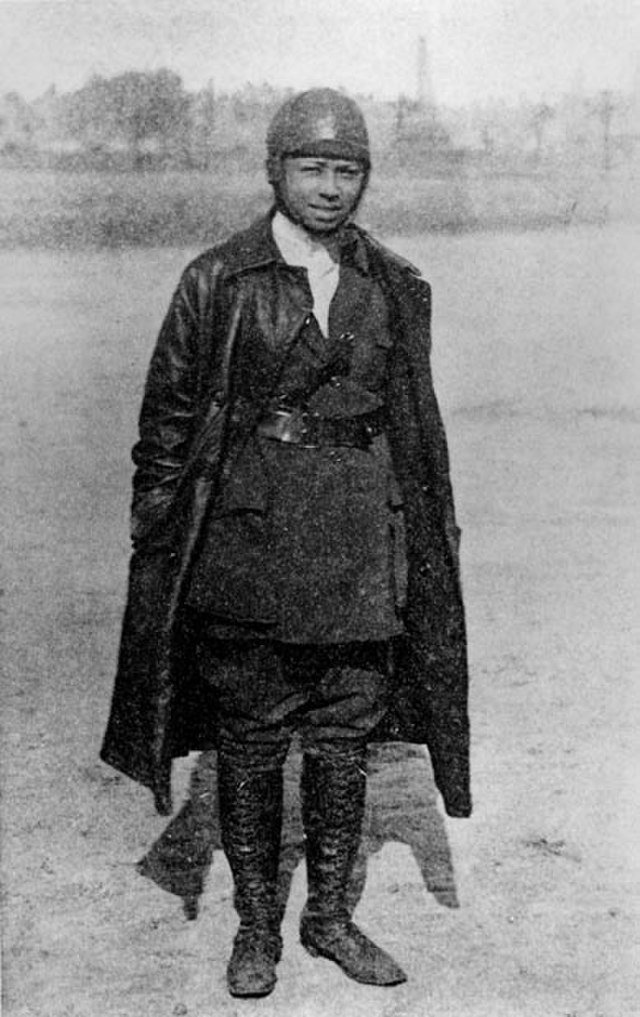

Bessie Coleman: History-Making Flying Ace

In the late summer of 1922, a Curtiss JN-4 Jenny biplane roared over a crowd on Long Island near New York City. The audience gasped as the plane soared through a complex routine of daredevil stunts. One moment the plane was high in the sky doing a figure 8, the next it dove impossibly close to the ground before recovering to fly back up and maneuver into another hair-raising feat. Clearly this was no ordinary pilot. Many onlookers, however, were surprised to find out how extraordinary they were. The pilot of this plane was none other than Bessie Coleman, the first Black woman to ever hold a pilot’s license. She was also the first woman of Native American descent to do the same. Her path to getting her license and becoming a history-making flying ace was not a clear or easy one, and is a testament to her commitment to achieving a dream despite the odds being stacked against her due to systemic racism and sexism.

On January 26, 1892, Bessie Coleman was born in Atlanta, Texas, into a family of sharecroppers, a common occupation of Black Americans in the area at that time. Her family moved to Waxahachie, Texas, when she was two in search of work, and that’s where she started school four years later, at the age of six.

Young Bessie had a four-mile walk to get to her one-room segregated school. She didn’t squander her opportunity for education, no matter how difficult it was to get to school, and developed a love for reading and math. Life in America didn’t always allow for poverty-stricken African Americans to focus on school, however. Bessie’s school routine was interrupted every year by the cotton harvest, during which she had to work along with her family at a young age. When sharecropping wasn’t making ends meet in Texas, her father left his family to move up to Oklahoma to find more work close to where his Cherokee grandparents originated. While Bessie’s family struggled in Texas, she still managed to get a scholarship when she was twelve to attend the Missionary Baptist Church School, where she went until she graduated at eighteen.

“I found a brand new world in the written word. I couldn’t get enough,” Bessie said. “I wanted to learn so badly that I finished high school, something very unusual for a black woman in those days. The teachers I had tried so hard. I don’t wish to make it sound easy, but I decided I wanted to go to college too. Since my mother could not afford college, I took in laundry and ironing to save up the tuition money.”

The money didn’t last long, however, and she had to leave Oklahoma Colored Agricultural and Normal University before she could finish. She moved up to Chicago to live with her brothers a couple years later, and this was where her life would change.

Bessie worked as a manicurist at the White Sox Barber Shop in the city. It was there she first heard returning World War I soldiers tell their tales about flying in the war. Day after day she would listen to them while they got their hair cut. Night after night she would relay the tales to her brothers, obsessed with the idea of flying through the wide-open sky, untethered to the ground, out of reach of everyone below. She knew this was what she was born to do. There was one problem, however.

No American flight schools at that time would admit a Black woman. Bessie’s gender and race were both against her.

That didn’t matter. A technicality like that wouldn’t stand in Bessie Coleman’s way. She got a second job in a chili parlor to save up more money to pursue her dream. Even having saved a substantial amount, however, no school would take her. One of her brothers teased her, saying that French women were better than Americans because they could fly. This goading, combined with encouragement from the millionaire founder of the Chicago Defender newspaper, Robert S. Abbott, inspired Bessie to look at flight schools in France, which admitted women. Once Abbott found out about her plans, he publicized her dream in his paper, and gave her funding from the Defender. Once word got out, Jesse Binga, who founded the first African American bank in Chicago, offered his support as well.

With the blessings and dollars of two of America’s first Black millionaires behind her, Bessie learned how to speak French and arrived in Paris on November 20, 1920. She was the only person of color in her aviation class, and one of the difficulties she faced in school was learning to fly in a biplane known to fail mid-flight, the French Nieuport 564. She saw one of her classmates, flying the same type of plane, crash and die while she was training, which was a shock. Yet still she stayed the course, and on June 15, 1921, she earned the honor of being the first Black woman and the first woman of Native American descent to receive a pilot’s license, an international pilot’s license at that.

She didn’t stop there. Knowing there were limited options to make a living flying, she took additional lessons from a French flying ace to learn how to be a stunt pilot. Upon her return to the United States in September 1921, she was inundated with reporters and attention. Americans of all races celebrated her as the first African American aviatrix, including a large white audience; ironic, since they didn’t seem to want to support her journey up to that point.

Bessie spent the next couple years traveling in Europe, learning more stunts and perfecting her aviation skills. In 1922, she began her career as a stunt pilot in air shows. She flew before crowds of thousands, performing stunts that thrilled and shocked audiences. Over the next five years, she performed at venues across the country, but absolutely refused to do any show at which African Americans were barred from the audience. Bessie was very vocal to encourage other Black men and women to fly, and was often criticized for her outspokenness and flamboyance. Her stunts were acceptable in the air, but apparently were too much to handle on the ground.

Stunts didn’t always go smoothly. Once, early in her career, Bessie’s plane stalled during flight and crashed, breaking her leg and three ribs. It took her a year to recover. Her final flight took place on April 30, 1926, in Jacksonville, Florida. She was preparing for a show the next day, in which her agent and mechanic William D. Willis would pilot the plane and she would make a parachute dive. They did a practice flight in a plane that was in questionable condition so Bessie could see the land where she would be jumping. Somehow, a stray wrench ended up falling into the gears of the plane. The plane went into an uncontrolled spin and plummeted toward the ground. Bessie, who wasn’t wearing a seatbelt, was thrown from the plane about 2,000 feet above the ground and fell to her death. Willis was unable to gain control of the plane and went down with it. The plane exploded on impact, killing him as well.

While most of the country’s media didn’t carry the news of Bessie’s death, she was greatly mourned in the African American press. Ten thousand people came to her funeral in Chicago, which was presided over by civil rights activist Ida B. Wells.

“The air is the only place free from prejudices,” Bessie once said. “I knew we had no aviators, neither men nor women, and I knew the Race needed to be represented along this most important line, so I thought it my duty to risk my life to learn aviation.”

Bessie paved the way for other Black aviatrices and was admired by many, including Mae Jemison, the first African American astronaut, who said, “I point to Bessie Coleman and say here is a woman, a being, who exemplifies and serves as a model for all humanity, the very definition of strength, dignity, courage, integrity, and beauty.”