Pliny Moody's Turkey Tracks, or, Could You have Dinosaurs in Your Backyard?

This article was publishing in Prehistoric Times Magazine last year. It was a lot of fun to research and write, especially since I got to see the slab of footprints firsthand at the Beneski Natural History Museum in Amherst, MA.

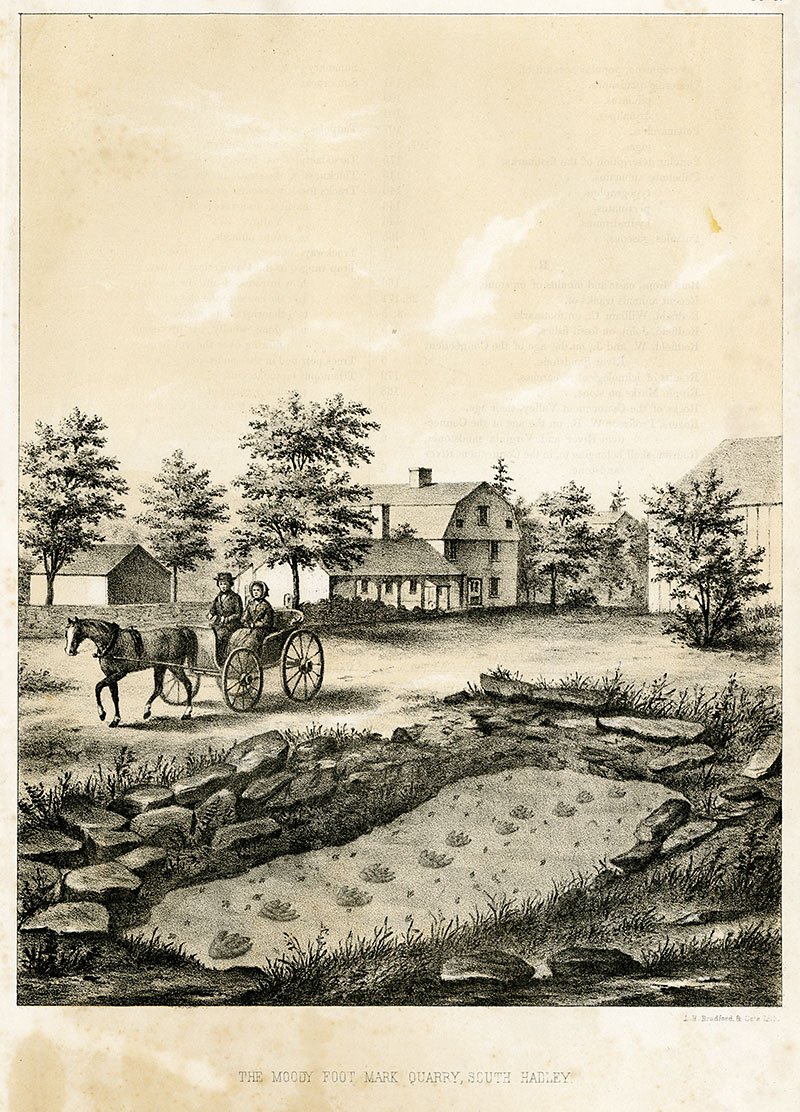

Pliny Moody, like many other twelve-year-old boys in 1802, spent the crisp, damp mornings of spring plowing his family’s fields in the small town of South Hadley, Massachusetts. Melting snow and vernal rains made the soil heavy, and great chunks of sandstone from the Connecticut River Valley’s ancient past cropped up all over the field. It wasn’t easy work, and Pliny had to stop to heave rock after rock out of the way. The labor may have kept him warm on a chilly morning, but being still a boy, he was surely impatient to be done with the job, and the interruptions didn’t help. There was nothing to be done, however. His family had to make a living and eat, and this was the land they had to work with.

Suddenly, Pliny’s plow hit an especially large slab of sandstone. As he perhaps rolled his eyes or sighed with frustration while he stopped to see how difficult it would be to get this rock out the way, it wouldn’t have occurred to him that the next few moments would put him into paleontological history.

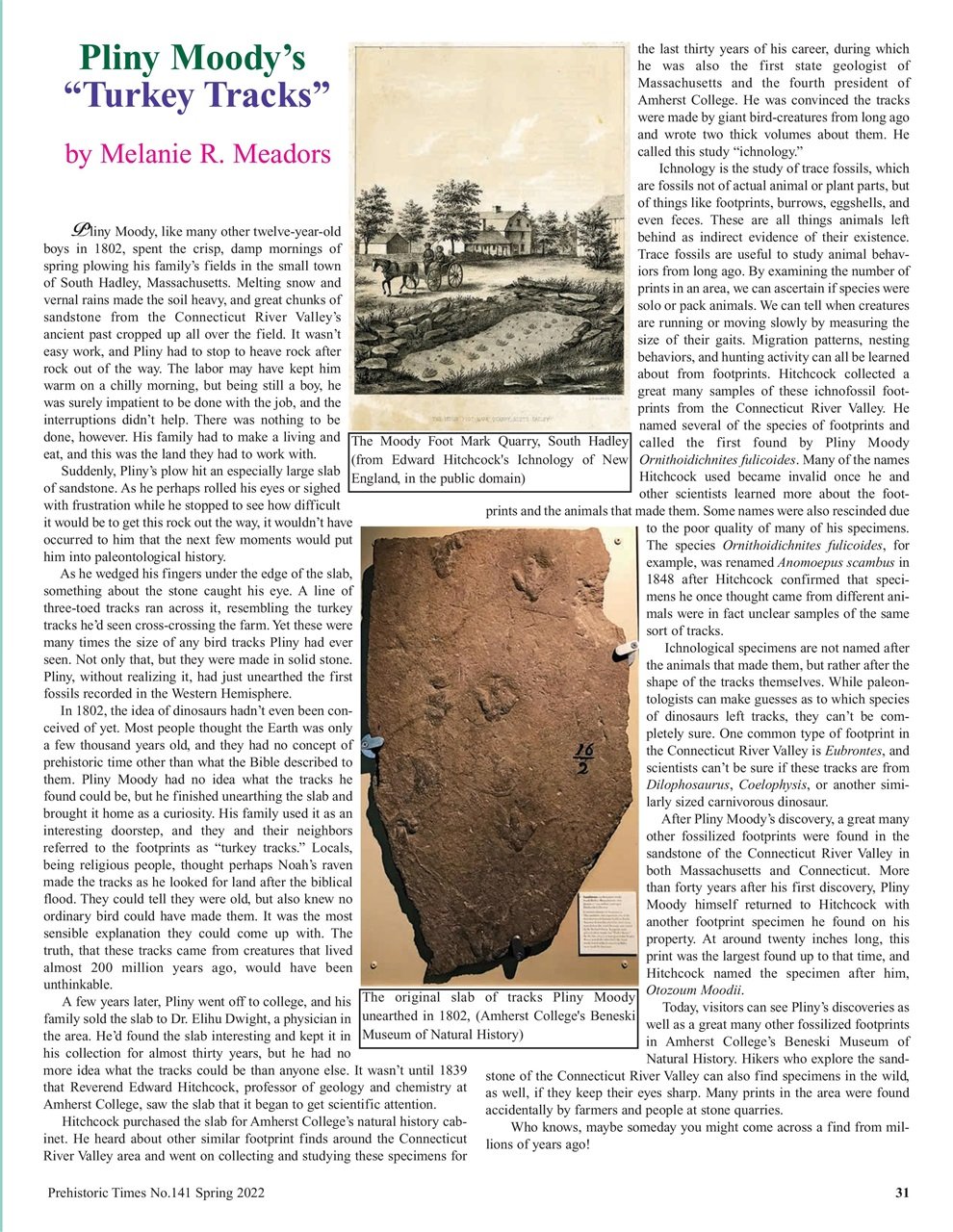

As he wedged his fingers under the edge of the slab, something about the stone caught his eye. A line of three-toed tracks ran across it, resembling the turkey tracks he’d seen cross-crossing the farm. Yet these were many times the size of any bird tracks Pliny had ever seen. Not only that, but they were made in solid stone. Pliny, without realizing it, had just unearthed the first fossils known in the Western Hemisphere.

In 1802, the idea of dinosaurs hadn’t even been conceived of yet. Most people thought the Earth was only a few thousand years old, and they had no concept of prehistoric time other than what the Bible described to them. Pliny Moody had no idea what the tracks he found could be, but he finished unearthing the slab and brought it home as a curiosity. His family used it as an interesting doorstep, and they and their neighbors referred to the footprints as “turkey tracks.” Locals, being religious people, thought perhaps they were the footprints of Noah’s raven. They could tell they were old, but also knew no ordinary bird could have made them. It was the most sensible explanation they could come up with. The truth, that these tracks were from creatures that lived almost 200 million years ago, would have been unthinkable.

A few years later, Pliny went off to college, and his family sold the slab to Dr. Elihu Dwight, a physician in the area. He’d found the slab interesting and kept it in his collection for almost thirty years, but he had no more idea what the tracks could be than anyone else. It wasn’t until 1839 that Reverend Edward Hitchcock, professor of geology and chemistry at Amherst College, saw the slab that it began to get scientific attention.

Hitchcock purchased the slab for Amherst College’s natural history cabinet. He heard about other similar footprint finds around the Connecticut River Valley area and went on collecting and studying these specimens for the last thirty years of his career, during which he was also the first state geologist of Massachusetts and the fourth president of Amherst College. He was convinced the tracks were made by giant bird-creatures from long ago and wrote two thick volumes about them. He called this study “ichnology.”

Ichnology is the study of trace fossils, which are fossils not of actual animal or plant parts, but of things like footprints, burrows, eggshells, and even feces. These are all things animals left behind as indirect evidence of their existence. Trace fossils are useful to study animal behaviors from long ago. By examining the number of prints in an area, we can ascertain if species were solo or pack animals. We can tell when creatures are running or moving slowly by measuring the size of their gaits. Migration patterns, nesting behaviors, and hunting activity can all be learned about from footprints. Hitchcock collected a great many samples of these ichnofossil footprints from the Connecticut River Valley. He named several of the species of footprints and called the first found by Pliny Moody Ornithoidichnites fulicoides. Many of the names Hitchcock used became invalid once he and other scientists learned more about the footprints and the animals that made them. Some names were also rescinded due to the poor quality of many of his specimens. The species Ornithoidichnites fulicoides, for example, was renamed Anomoepus scambus in 1848 after Hitchcock confirmed that specimens he once thought came from different animals were in fact unclear samples of the same sort of tracks.

Ichnological specimens are not named after the animals that made them, but rather after the shape of the tracks themselves. While paleontologists can make guesses as to which species of dinosaurs left tracks, they can’t be completely sure. One common type of footprint in the Connecticut River Valley is Eubrontes, and scientists can’t be sure if these tracks are from Dilophosaurus, Coelophysis, or another similarly sized carnivorous dinosaur.

After Pliny Moody’s discovery, a great many other fossilized footprints were found in the sandstone of the Connecticut River Valley in both Massachusetts and Connecticut. More than forty years after his first discovery, Pliny Moody himself returned to Hitchcock with another footprint specimen he found on his property. At around twenty inches long, this print was the largest found up to that time, and Hitchcock named the specimen after him, Otozoum Moodii.

Today, visitors can see Pliny’s discoveries as well as a great many other fossilized footprints in Amherst College’s Beneski Museum of Natural History. Hikers who explore the sandstone of the Connecticut River Valley can also find specimens in the wild, as well, if they keep their eyes sharp. Many prints in the area were found accidentally by farmers and people at stone quarries.

Who knows, maybe someday you might come across a find from millions of years ago!