Look, Don't Touch: But Why?

We've all seen the signs at museums: "Don't touch." Which makes sense. As much as we might want to experience the dramatic brush strokes of an Impressionist painting in a tactile way, we don't want to wear the paint off. Most people get that. Anything that has paint or color or ink on it, logically it makes sense that touching means damage. Beyond that, though, things get more complicated.

I'm currently researching part of a French priory that was relocated to America in the 1930s for a larger project. This structure is called the Chapter House and it resides at the Worcester Art Museum in Worcester, Massachusetts. It was made of limestone bricks in the twelfth century as part of the Le Bas Nueil Priory. Its entryway would have faced the Benedictine priory's cloister, but now it looks upon the Art Museum's Renaissance courtyard. Monks would have met in the Chapter House daily to discuss priory business before dispersing to their duties elsewhere. While the monks were expected to be quiet in the rest of the priory, in the chapter house they assembled and spoke, read a chapter of the priory rules (hence the name "chapter house"), received important guests, and listened to new monks take their vows. The Chapter House had people coming and going for hundreds of years until it was decommissioned during the French Revolution, and would have felt the touches of possibly thousands of people. So why now do we have this sign? Surely a building is more sturdy and lasting than a painting or other piece of art, right? Well, it is... and it isn't

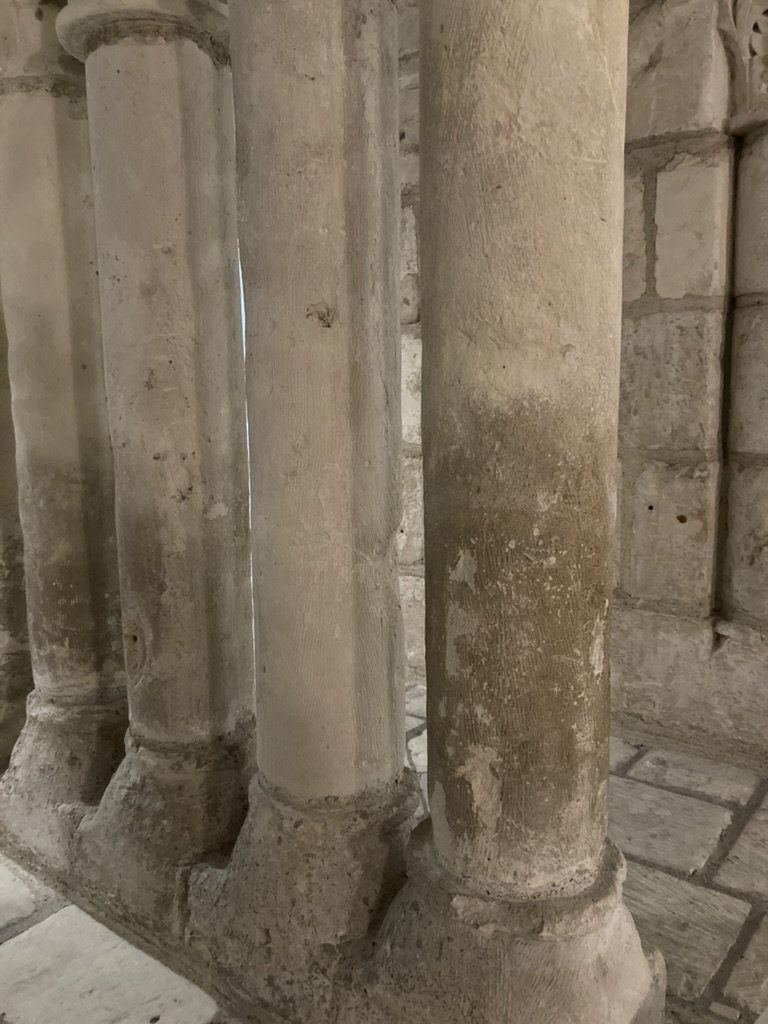

If you look up at the vaulted ceiling at the Chapter House--the only of its kind in America--you'll see the white limestone in its pristine-ish glory. It's a lovely pale cream color. Everywhere about five feet above the ground and up, the walls are like this as well. But below that in several spots, that creamy limestone gives way to this:

Twelve years ago, in 2012, conservators put much research and effort into cleaning the walls of the Chapter House, using a special mixture of chemicals that would clean oils and dirt from the walls while not damaging the limestone underneath. They restored the stone to its former glory, but left one stone untouched, so museum visitors could see the difference. It's pretty grody.

Since 2012, a lot of visitors have passed through the Chapter House and, despite the signage, many of them have touched the walls and columns. I've not had to see people doing this to know that it's happened. Why not? Because the walls in some spots have turned black and shiny with the oil from people's skin. This is just over the course of twelve years! Something I've found amusing is that there are two distinct bands of discoloration. One is low, where kids can't help themselves and have to touch something. Then there is a lighter band, and above that, another darker one where adults have touched it. All of this is from the natural oils in people's skin. Imagine what the Chapter House--or indeed, sculptures and even the formations in limestone caves, which also have signage for people to keep their paws off--would look like if every visitor touched the stone? Limestone is particularly susceptible to discoloration because the oils penetrate the surface and absorb into the stone itself because it is porous. This makes it extremely hard to clean. The stone can't be washed with soap, because the soap itself will discolor the stone. Some cleansers will cause a chemical reaction with the stone, eating away at it. With something like a building or sculpture with delicate features carved into it, this can be devastating.

Conservators have put a lot of work into developing safe ways to clean limestone, but the more they have to clean it, the more the stone will wear away, just with the act of wiping or spraying. The best course of action is prevention; in this case, the rule of "look, don't touch."

Buildings like the Chapter House at the Worcester Art Museum have lasted hundreds of years and have traveled over a thousand miles so people like you and me can enjoy them. With our cooperation, they can last hundreds more years, bringing generation after generation a sense of wonder at this bit of European history that lives in the US.