Reading Like a Writer: 'Washita Love Child' and Author Lens

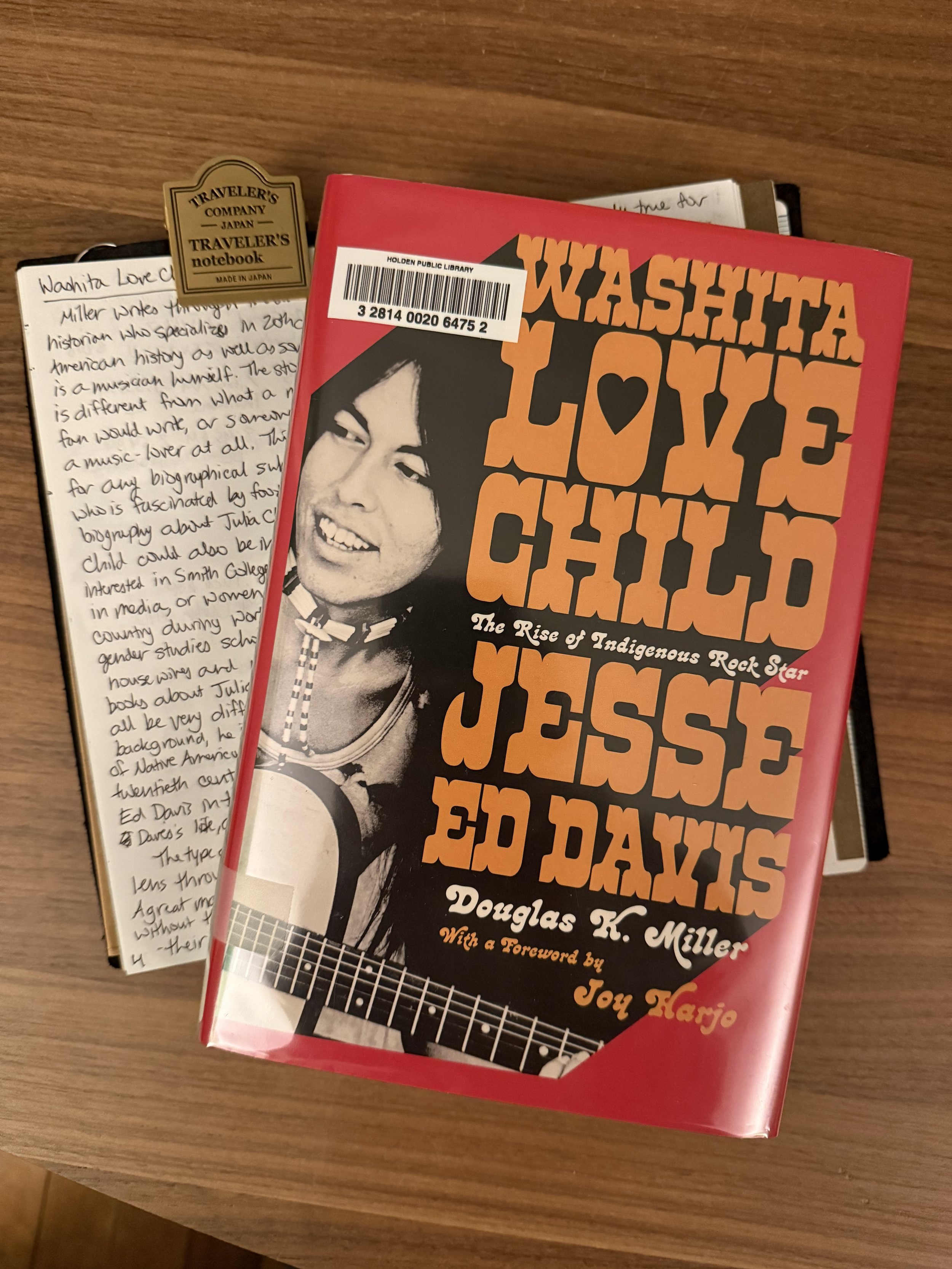

In this “Reading Like a Writer,” I’m going to look at Washita Love Child: The Rise of Indigenous Rock Star Jesse Ed Davis, by Douglas K. Miller. What is “Reading Like a Writer,” you might ask? Check out the overview post here.

Washita Love Child is the biography of musician Jesse Ed Davis, a guitarist who played with people like Conway Twitty, Eric Clapton, George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Rod Stewart, and many more. His career ranged from the 1960s through the 1980s. He was known not only for his skill with guitar, inspiring many who came after him, but because he was Indigenous, growing up at a time when the integration of Native people into modern American culture was a hot topic. This biography is written, like most others, through a particular lens, and that is the topic of this article.

The lens through which something is written is a lot like bias, but can be different. Bias is something we all have, and it informs all of our work. I (and many others) would argue that there is no such thing as an “unbiased” work, because we all bring our backgrounds into what we do. We all have things we come into our work with, simply because we are human. Our ethnicity, culture, the society we grew up in, our socioeconomic background, our race, education, gender, and our family and community attitudes all shape the way we see the world, in both conscious and unconscious ways. This isn’t a necessarily bad thing, but it’s something we should be aware of, especially if we are writing about people who have different backgrounds from us. Our experiences might make it almost impossible to truly understand certain other people. Their motives might be alien to us, and so it’s important to have other people read our pieces to make sure we haven’t made any judgements that are not accurate. For example, I went on a service project trip where I built houses with several others for people who were very economically underprivileged. Coming from a working class family, my background was much different from others in my group whose parents were doctors and lawyers. When a little boy from the community we were helping told us he wanted a Nintendo for Christmas, the group was surprised. During our reflection time that evening, they commented on it. “These people are so poor and practically going hungry. Why would that boy want a Nintendo instead of food?” To me, it was no surprise at all. I answered, “Because he’s a little boy, and that’s what little boys want for Christmas. I’m betting his parents are happy he wants that, like a normal kid, rather than worrying about the family’s food.” I could see that because of my background. The others, with very different backgrounds, didn’t understand at first. We all brought different biases to the situation, and we saw things differently.

Lens is a little different. Where our biases are often times unconscious and in the background of our thoughts, lens can be used intentionally. It can be a tool to make your writing different from someone else’s. Two people (and more!) can write a biography about the same subject, and end up with drastically different books depending on the lens through which they are viewing their subject. Douglas K. Miller could have written his book through the lens of a musician. He could have written it through the lens of a fan, or of social change, or of someone who grew up in the 70s. Instead, he uses his area of expertise to write about Davis through the lens of a historian who specializes in 20th century Native American history. Other aspects come into play as well—Miller is a musician and clearly a fan of Davis’s work, but where he shines and what makes the book his own is the historical lens. The story he tells is different from what a non-academic fan would write, and also different from someone who was not a music-lover.

This works for whatever subject you choose. Someone who is fascinated with food could write a biography about Julia Child. But Child could also be interesting to someone studying Smith College graduates, women in media, or women who served the country during World War II. Historians, women’s studies scholars, chefs, journalists, housewives, and more could all write books about Julia Child through their specific lenses, and they would all be different.

Because of Miller’s background, he is able to create a portrait of Native American life in the 19th and 20th centuries and then place Jesse Ed Davis into that context. This helps make Davis’s life, actions, decisions, and attitudes make sense. If a musician were to write Davis’s biography, perhaps they would focus more on Davis’s style of music and what influenced him, perhaps looking more at his instruments and taking apart his songs. Both would have been equally valid lenses through which to see Davis’s life. If we stick with what we are good at, however, and how we see the world instead of trying to force ourselves to write about things completely foreign to us, the story really becomes ours—unique to us. No one else could have written Davis’s story like Miller did. In that way, you too can write a completely unique book about someone, even though other books have been written about your subject. Think about a subject you might want to write about, and then think about yourself a bit. What does your subject look like through your lens, due to your background or education? What part of your subject’s life resonates with you most? Why?

The type of research you do can also inform the lens through which a biography is told. A great many biographies have been written without the author speaking to a single source—their sources are all in the archive, or in books. This is obviously true for people who have been dead for a long time, but it actually doesn’t have to be. An author could interview people about how a subject’s work has influenced them today, or how their work affected their field or shaped their nation. Likewise, there are authors who write about people who are alive, yet still don’t talk to anyone. They rely on written sources for a variety of reasons. For example, perhaps their subject doesn’t endorse their work. J.D. Salinger reportedly not only refused to grant a biographer an interview with him, but went on to file a lawsuit to prevent any of his colleagues and friends from speaking to the biographer as well. The author had to do what he could to create a portrait of Salinger’s life.

Douglas K. Miller

When researching Washita Love Child, Miller did over a hundred interviews with Davis’s friends, family, and colleagues. This gave the book a much different perspective than it would have had if Miller relied solely on written sources or even just existing interviews performed by others. Because Davis embellished many stories about his past, and other stories changed as time passed, having all these interviews and all these perspectives allowed Miller to show the reader a more well-rounded picture. This really makes the case for biographers going out and doing the work of talking to people rather than solely relying on the archives. Yes, people can be unreliable sources, but when you interview enough people, you can create a more clear, multi-faceted, and nuanced story. What if you ware writing about someone who was alive hundreds of years ago? Think back to what interested you about your subject to begin with. What is the lens through which you are looking at them? Who are experts about that field or topic or community? Try interviewing them and see if that helps. Try to find contemporary sources that perhaps support or oppose your subject’s work. Even if you can only access written sources, try to collect as many perspectives as you can in order to create a more complete picture. Then you can pick and choose the perspectives that help you make your argument.

Being aware of the lens through which you are writing allows you to write a narrative that is different from everyone else’s, and being aware of that lens allows you to use it in the most effective way. The next time you read a biography or other book, ask yourself what the author’s lens is. Once you identify it, see if you can tell how they used their lens, or if they did at all. Often, if you read a biography that seems scattered or chaotic, or you ask yourself what the author’s point is, it might be that they didn’t have the focus that working with a lens allows. Having a lens allows you to make a point and to stick to it. It also makes giving an elevator pitch so much easier.